The Currents of Tradition

The Currents of Tradition

An Armenian composer revives the ancient music of his people through his award winning Ensemble.

One of the most active figures in Armenia’s musical life, Levon Eskenian has performed both as a solo pianist and chamber musician in styles ranging from early baroque to contemporary music in Europe, the Middle East and Armenia. He recently founded The Gurdjieff Ensemble to play ‘ethnographically authentic’ arrangements of the Armenian folk repertiore. Their debut album on ECM, Music of G.I. Gurdjieff, was widely acclaimed, and won an Edison Award for Album of the Year.

EPK FOR THE GURDJIEFF ENSEMBLE'S LATEST RELEASE, COURTESY OF ECM RECORDS

FINDING GURDJIEFF

What inspired you to form the Gurdjieff Ensemble?

The story of the Ensemble really begins with my discovery of the piano compositions of Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann.

George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff was born in Armenia, and known to many in the West as one of the major spiritual figures of the 20th century. It is said that experiences in Gurdjieff’s childhood awoke within him an irrepressible need to understand the mystery of human existence. Early in his life, he and a group of fellow ‘seekers of truth’ set out on a search to understand the aim and significance of life on earth, and in particular man’s place in the cosmos.

This search began in Armenia, and took him throughout the Middle East and many parts of Central Asia, India and North Africa. Along these travels, he witnessed a myriad of folk music and dance traditions, and possessed an extraordinary capacity for remembering the melodies he heard around him. In the 1920’s, he composed some 300 pieces and fragments for the piano inspired by this music in the manner of dictation to his pupil, Thomas de Hartmann, the Russian pianist and composer.

When I first heard this music, I recognized it had its roots in the Middle East, as well as in Armenia. I believe you can find the psychology of the Armenian people in this music... and so I thought to myself, how would it sound if we were to bring it back to the authentic instruments, to the original sounds that Gurdjieff might have heard during his journeys?

For example if we have a Gurdjieff Kurdish shepherd melody, we could learn what the Kurdish shepherds commonly played —the saz and the ney, simple instruments, one instrument accompanying the other— and explore the same for what the Arabs used, the oud and kanun and daf, and the Armenians using the duduk as a solo intrument, etc..

So after researching the traditional instruments of these cultures, and studying their different interpretations and styles, I arranged Gurdjieff's piano music back to these original sounds. Then I began to listen to different traditional musicians from all over Armenia, and invited those I felt could get really deep into this music to form an ensemble.

Then the great Armenian composer Tigran Mansurian heard us at one of our performances, and became very excited; he asked us for a recording of the concert, which he presented to Manfred Eicher at ECM. The cellist Anya Lechner also mentioned us to Eicher, who then expressed interest in making an album with us.

We first recorded with ECM in 2011, and this recording then made its way all around the world. We received invitations from many different music festivals —we've performed at major festivals and venues in more than 15 countries— and are still playing this program today.

Listen to the original piano version of Gurdjieff's 'Assyrian Women Mourners', contrasted with Levon's arrangement for the Ensemble:

Although the pieces on this album are drawn from many different lands and cultures, I find the mood is very consistent, and as a whole it feels very unified. What do you think enables this music to work together so seamlessly, and what was it that Gurdjieff might have been looking to express through it?

I think what we find here is the character of Gurdjieff himself—that this music has passed through him as a composer. He taught that ancient music and ancient arts were not for 'liking' or 'disliking', but were meant for understanding. Such music has been passed down to us through centuries of time, from the very beginnings of humanity. It communicates through the powers of sound and silence, which has a mystery in it—it invites you to reflect on the deeper meaning behind things, and helps to connect you with your inner self.

This kind of music can still be found in villages today; I've encountered such in Armenia. Yet I’ve also found that when music comes to the modern context of the city, it changes. It becomes music for the stage, something used simply as a tool for entertainment... but what was music created for from the very beginning? What true meaning has it in itself?

If you go to a village, you may hear a mother singing a lullaby for a child. Or dance music at a wedding; or you go to a funeral and hear duduk players performing at the ceremony. And that's not music for entertainment anymore, or for making money. It is for compassion. And those playing this music are truly there—they are performing and living for that moment.

So things like work music, ritual music, they touch a deep part of the person listening... because they are very true and un-artificial. From the beginning they were never made for the purpose of pure entertainment or profit.

Because of this difference between the traditional purpose of music and the common approach today, it can be a challenge to take folk music out of its natural setting and bring it to a stage. This can be a very dangerous thing to do I think, if you don't create an atmosphere that keeps the essence of the music alive.

A PERFORMANCE OF GURDJIEFF'S CHANT FROM A HOLY BOOK AT THE EDISON AWARDS CEREMONY IN HOLLAND

KOMITAS

Recently the Ensemble made its second recording with ECM, focusing on the music of another Armenian composer, Komitas. Can you say a little about the inspiration and concept behind this recording?

Well first I should say that Komitas is in fact a relative in blood with me, because my mother's family is from Kütahya, the same village that he was. So I have this connection to him, and in this way his music is very close to my soul, because it's Armenian music, and also because it's music that has its roots in very ancient times.

Is it true that this recording, similar to the Gurdjieff album, was recreated solely based upon piano works?

Yes, but there is a difference between the piano works of Gurdjieff and those of Komitas—while Gurdjieff remembered the melodies he heard and later dictated them to Thomas De Hartmann, Komitas (being himself a composer) directly wrote down the music he heard around him.

These pieces are very unique, in the sense that he didn't simply write melodies and then harmonize them in the traditional style of Western classical music, but tried to recreate the rhythms and timbres of Armenian instruments on the piano. He went into great detail, specifically describing what sounds and types of instruments the pianist should imagine and emulate.

PORTRAIT OF KOMITAS BY S. MURADYAN

Why do you think Komitas chose to compose the music he heard for the piano?

I think the main reason was to be practical, to be able to share this music with the West. Yet for pianists today who may have never heard these instruments or styles, there's the dilemma of how to draw inspiration from these references; this was one of the reasons why I wanted to go back and recreate the sounds that Komitas originally heard—so that more people could really understand this music, and connect with it more deeply.

As a composer Komitas is still not very well known in the West. Can you speak more about his background?

Komitas received a rich musical education in both the Western classical tradition —in Berlin, with very great teachers of the time— as well as in Armenian spiritual music, as a monk at the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, of the Armenian Church. He also studied early european music, and was in fact one of the first ethnomusicologist composers, along with Bela Bartok.

This work began in his youth when he was studying in Etchmiadzin, and was struck by the songs pilgrims sang who came to the Church from different parts of Armenia. Hearing the people of each village singing their own traditional songs, he started to document hundreds and thousands of songs from different parts of Armenia.

He also researched the anthropological dimensions of this music—classifying different folk songs, spiritual songs, songs for dance, work, funeral songs, etc. He realized that through studying this music one could understand the culture of its people.

So in classical music he created a new style, introducing new rhythmic patterns and harmonies based on Armenian music. He moved away from the purely major and minor tonal system, and developed a new way of harmonizing, which was born from the sounds of Armenian music. So he tried to stay true to the environment, the musical atmosphere coming from the Armenian music itself.

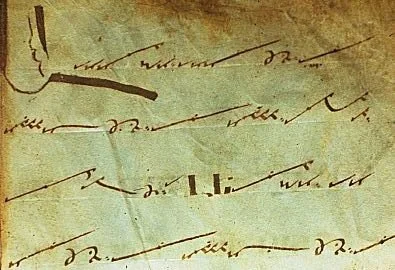

KHAZ 12TH CENTURY MANUSCRIPT

He was also a decipherer of Khaz, the old Armenian notation system, which was created beginning in the 9th century to notate Armenian sacred music.

Armenia was the first country to adopt Christianity in 301, and the music of the different traditions that existed before Christianity were kept, and Christianized. Through this Komitas found the connection between sacred Armenian music and folk music, which in his words are like brothers and sisters, because Armenian sacred music was derived from Armenian folk music. Even today you can recognize this continuity. When I listen to say a liturgy for example, I can also hear that this melody may have come from a plow song.

And so as an ethnomusicologist Komitas did a tremendous service to his culture, collecting thousands of melodies, especially from the western part of Armenia, where later during the genocide many were killed, and much was lost. Without this work I'm certain we could have lost all of these traditional songs, music that reaches back thousands of years. That's why Komitas is so important for Armenians, and also for our greater humanity, because through him we are able to reconstruct these ancient songs and traditions.

An example of this is one of the pieces on the album called Msho Shoror. It's comprised of a series of dances that Armenians used to perform while on pilgrimage to Surb Karapet Monastery, which was a marvelous cathedral.

SURB KARAPET MONASTERY

Pilgrims came from different villages all across the country and danced to this music, which through his research Komitas concluded came from Armenia's pagan times. I've done my own research on this as well, and discovered that prior to Christianity this cathedral was a temple dedicated to the Armenian god Vahagn, which was the god of light and sound. So in my opinion this music comes from those times.

Then in the 1920's after the genocide, Surb Karapet was completely destroyed. Yet what we have through this music, through Komitas, is the essence of what it was. And by reconstructing these piano pieces, we can share this music and culture with the world that would otherwise be lost to time.

HARMONY

You mentioned the difficulty of preserving the essence of this music when bringing it into a different social and cultural environment—how did you accomplish this in the studio, and in your live performances?

Well, I don't know if I’ve accomplished that... (laughs). I think first of all it comes from the composers. We can acknowledge this with Gurdjieff, and we can say the same for Komitas too. Their work was so true that if you follow them, and try to understand and be true to them, you will become part of this current, something that goes back deep into ancient times.

That current was created by our ancestors as they interacted with life and nature. Then it passed through Gurdjieff, and also through Komitas. So when we try to be true to them, true to the content and the essence of their music, then we also become a person who passes this current on.

I think this is the most important thing, to not disrupt the flow of that current when playing music in this way. This is in fact related to Gurdjieff's philosophy, which is based on being very attentive—his work tries to wake you up from a mechanical way of living, and for musicians, a mechanical way of playing...

PERFORMING KOMITAS AT MORGENLAND FESTIVAL IN OSNABRUEK

He taught that we should cultivate harmony within our three centers: our body, our mind, and our emotions, so that they are in balance, and working together.

If we lose attention in one of these parts, we become mechanical. Often times we move mechanically throughout the day when we walk and act, and through time we become rigid. Yet we do not begin this way, as the spontaneity and naturalness of children shows us.

So how to rediscover this harmony within the three parts of ourselves, while making music? To have our emotions be present, our mind be present, and to hear and feel the full range of the vibrations in the music? We are not so attentive to these details usually... but as Beethoven says, 'the vibrations on the air are the breath of God'.

I find classical musicians especially have this problem—many of us forget about the true meaning of music, because our instruments have a lot of technical aspects that constantly need to be addressed, and you can get caught up in this, and forget about the true meaning of what you are doing, which is simply about making music. But traditional musicians keep this understanding; they keep to the essence of making music.

There was in fact a period of time when I was doing research into the work and music of Gurdjieff that I wasn't able to listen to classical music at all, because I had this conflict within myself. I had to question everything, and ask myself, 'What is music for? What are the performing arts, and how should we approach them?' And so I've learned a lot from these projects, and from the folk musicians, and as a result of this work something within me has changed.

ANCIENT CHURCHES AND CATHEDRALS OF ARMENIA

MYSTERY AND UNDERSTANDING

How accurate do you feel the reconstructions you have created are to what this music originally may have sounded like?

Naturally they won't be 100% authentic, because we can't really know what it was truly like without being there ourselves... I was reading something the other day by René Jacobs, one of today's great conductors and interpreters of Bach, and he said: 'Important and necessary as it is to study what the performance of a piece was once like, it cannot be the basis of your interpretation. If that is all you consider, your interpretation will be a mere alibi, something that hides the fact you have no personality and imagination. Like Harnoncourt, I too think I can’t do authentic Bach – all I can do is authentic Jacobs.'

So we try to be true, we try to be objective as possible, but ultimately you can't create the same interpretation if you're not living in those times; if you're not driving an ox to plow the soil.

But regardless, I think with whatever forms we have from ancient times, we always need to refer back. We need to carefully try to understand them. As I mentioned, and as Gurdjieff says, ancient art wasn't created for liking or disliking. There's knowledge and wisdom encoded within it. Even if it's passed orally over many centuries, we have the structure and the form, and it's still held inside.

If you decipher very old folk songs for example, the words or the essence of what it was created for contains a very deep meaning. It encourages our connection with nature, and with our true selves. Today we think that humanity has developed, but what have we developed? Apart from maybe comfort and technological advancements, what have we developed in terms of truly understanding ourselves, and the mystery of our existence?

I think in ancient times humanity was much more into these questions. Understanding ourselves, our relation with nature, with God, with the cosmos.... everything comes from these questions.

So I believe we need to study the strands of culture that have come down to us —whether they are from Africa or India or Armenia— we need to be careful with them, and preserve them.

It's very heartbreaking right now to see all these monuments in the Middle East being destroyed. They are part of the culture of humanity, something that belongs to everyone. It's the same way I feel when I think of the 2,000 churches and cathedrals that were destroyed in Turkey, which was part of Western Armenia before the genocide.

I have tried to understand for myself how and why all of this could have happened, and what I've realized is that it's so important to appreciate and protect what we have from ancient times, and find new ways to share it with the world.

— www.gurdjieffensemble.com —