Wagner and Desire

Wagner and Desire

By SHANT ALAJAJIAN

Opening

All things partake in the Oneness of Reality and therefore all things are interconnected. The sacred threads that weave through the various art forms reveal this truth. The interconnectivity of the ancient art forms is best depicted in the paintings of the nine muses of Greek mythology, who dance in a circle with joined hands to the music of Apollo’s lyre. The 19th century German composer, Richard Wagner had excelled in the binding of all art forms into a coherent whole. Through his works, he delved to the essence of the human condition, and along the way, presented a synthesis of the arts such as had never been experienced before. In this short essay, we will explore some of the spiritual and philosophical inspirations for Wagner’s operatic works and how the underlying themes of the Will and Desire can not only shed light on our human drama but reveal the correspondence of music with Nature.

Apollo and the Nine Muses.—John Singer Sargent.

Buddhism and Schopenhauer

Often the profoundest insights into the mysteries of existence appear to us in the simplest of guises: a crimson-petalled rose, a fractured prism of light, the rotating symbol (e.g. Tai Chi and the Ouroboros). But intimations of such deep significance also appear to us through the most familiar of sounds. In many cultures the sounding of bells marks life’s transitions---from celebratory marriage bells to the sombre tolling of funeral bells. However, Buddhist temple bells (called Bonsho), have always carried the analogy of the impermanence of Man. The reverberations begin from an indefinable moment and resonate until dissipating into the silence from which it emerged. This interval comprises the totality of a person’s earthly life; a life which comes into being with a great cry, makes a noise in the world for a brief time, and comes to an end as its energy dims and diminishes toward Death. Such reminders of our transient nature impel us to regard life as valuable and intensely meaningful. It also reinforces the need to view ourselves with humility in the face of the cosmos.

The 19th century German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer was one of the first Europeans to encounter the ancient writings of Buddhism and Hinduism. These teachings informed his worldview and his contributions to philosophy. Although his understanding of these religious systems was not particularly orthodox, Schopenhauer became an instrumental philosophical link between the East and West—a divide much spoken about, but ultimately illusory in its deepest analysis. Schopenhauer’s incorporation of Buddhist and Hindu ideas heavily influenced the trajectory of Western philosophy as well as the life and work of German composer, Richard Wagner.

Many Buddhistic themes regarding reincarnation and karmic energies course through Wagner’s operas, particularly in Der Ring des Nibelungen (referred to here simply as The Ring Cycle) and Parsifal. In fact, many scholars, including a practicing Buddhist monk, have hypothesized quite compellingly, that Parsifal is in fact the final opera of the Ring Cycle.1 It is argued that several of the major characters from the Ring Cycle reappear in reincarnated form as the main actors in the Parsifal opera, having to counterbalance, through specific meritorious (kusala) karmic deeds, the evil or non-meritorious (akusala) karma they brought into being at the beginning of the drama. These Buddhist notions were not accidentally stumbled upon. Wagner became familiar with Buddhist writings through the works of Schopenhauer which he industriously read and reread throughout his life.

It should be noted that Wagner’s intentions for the Ring Cycle (including Parsifal) was the creation of what he termed a “Bühnenweihfestspiel” or “stage festival play”. Combining the sacred symbolism and ritual of ancient Greek stage tragedy, with the musicality of Beethoven and poetic genius of Shakespeare, and further informed by Buddhist-inspired metaphysics and philosophy, he aimed at a “total synthesis of the arts” (Gesamtkunstwerk). In his operatic works music, theater, aesthetics, philosophy, and mysticism hold hands and share the stage in portraying the human drama.

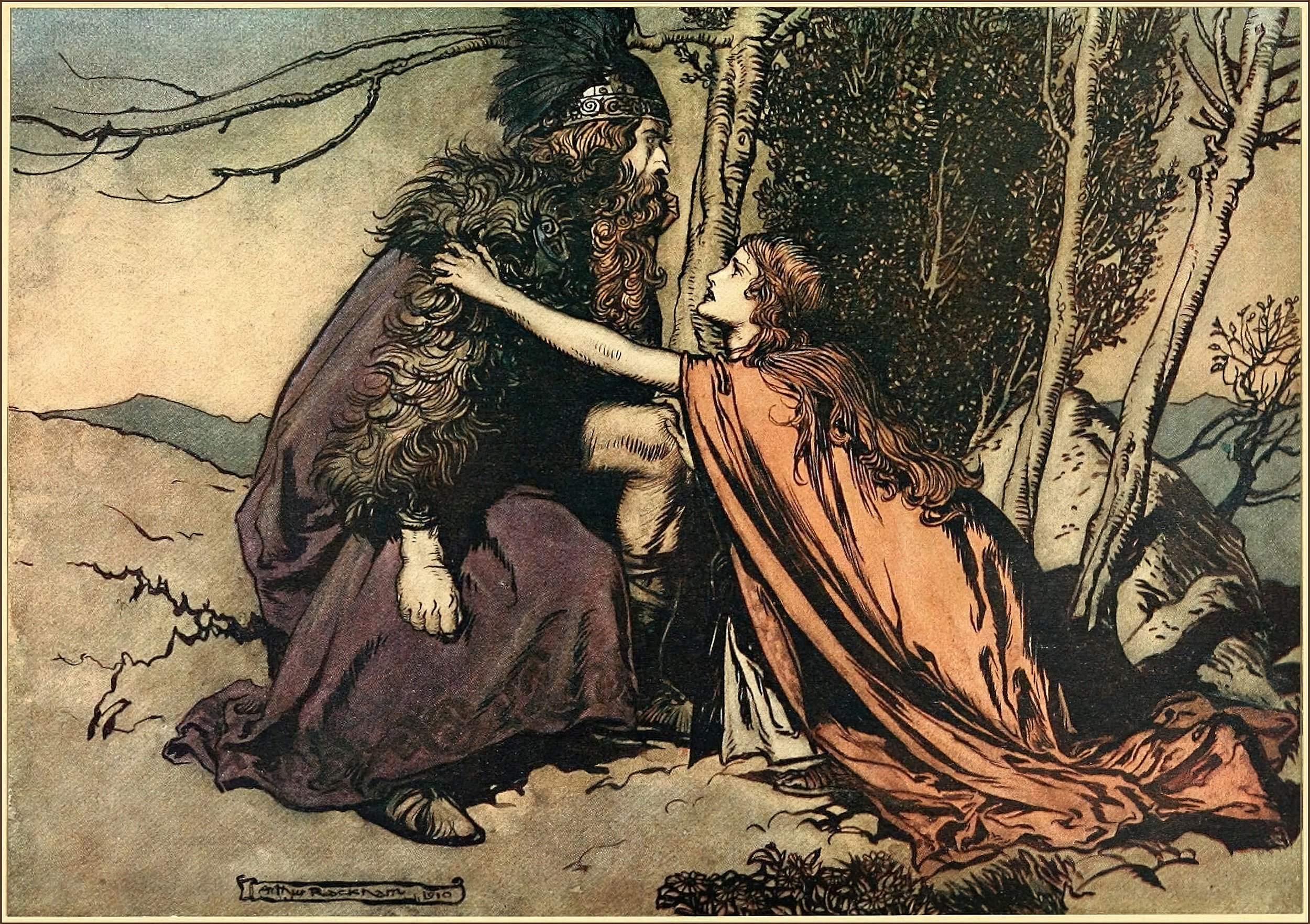

Brünnhilde and Odin from ‘the valkyrie’.—Arthur Rackham.

Metaphysics of Music

Of great interest to Wagner was Schopenhauer’s articulation of the metaphysics of music, and how well it captured the protean nature of Desire. A bold distillation of Schopenhauer’s extensive oeuvre can be summarized in the following two propositions: 1) music is the embodiment of the Will and 2) music and nature share a corresponding reality.<sup>2</sup> The Will can be unfolded to reveal its many facets: longing, desiring, yearning, craving. Schopenhauer argues that such willing reaches down to the innermost depths of our Being, in fact, constitutes it. After all, without the power of the Will as an elemental life force, we would cease to exist---for even the act of breathing itself is an expression of the Will to Life. However, an individual’s Will and its despotic claims on the world around it make it vulnerable to becoming attached to the things it claims dominion over. In Buddhist teaching these attachments are the fuel for negative karmic streams that lead us further from the attainment of Enlightenment and the pursuit of Nirvana.

Nowhere is our Will more beautifully and painfully described than in Schopenhauer’s example of listening to music. From the moment the melody begins, we are transported through the progression of notes and chords, willing the music to unravel in all its simplicity or complexity, and then resolve and close on the tonic (i.e., the final resolution note). If the melody ends on any note other than the tonic, the listener experiences a deep sense of dissatisfaction (the Will is temporarily thwarted) —this results in a tension that remains hovering without its fulfillment and release. The expressive interplay of chords and notes signifies the variegated emotions of the human condition, twirling and dancing and guiding the listener as she follows its musical movements; such movements as expressions of her own life and her own suffering—her dreams, ambitions, pains, fears, ecstasies, and joys. The piece of music articulates the endless desiring of the listener until the finality of the last breath, or the last note, resolves the life and the song. No Wagnerian opera presents Schopenhauer’s ideas so clearly and profoundly than Tristan and Isolde.

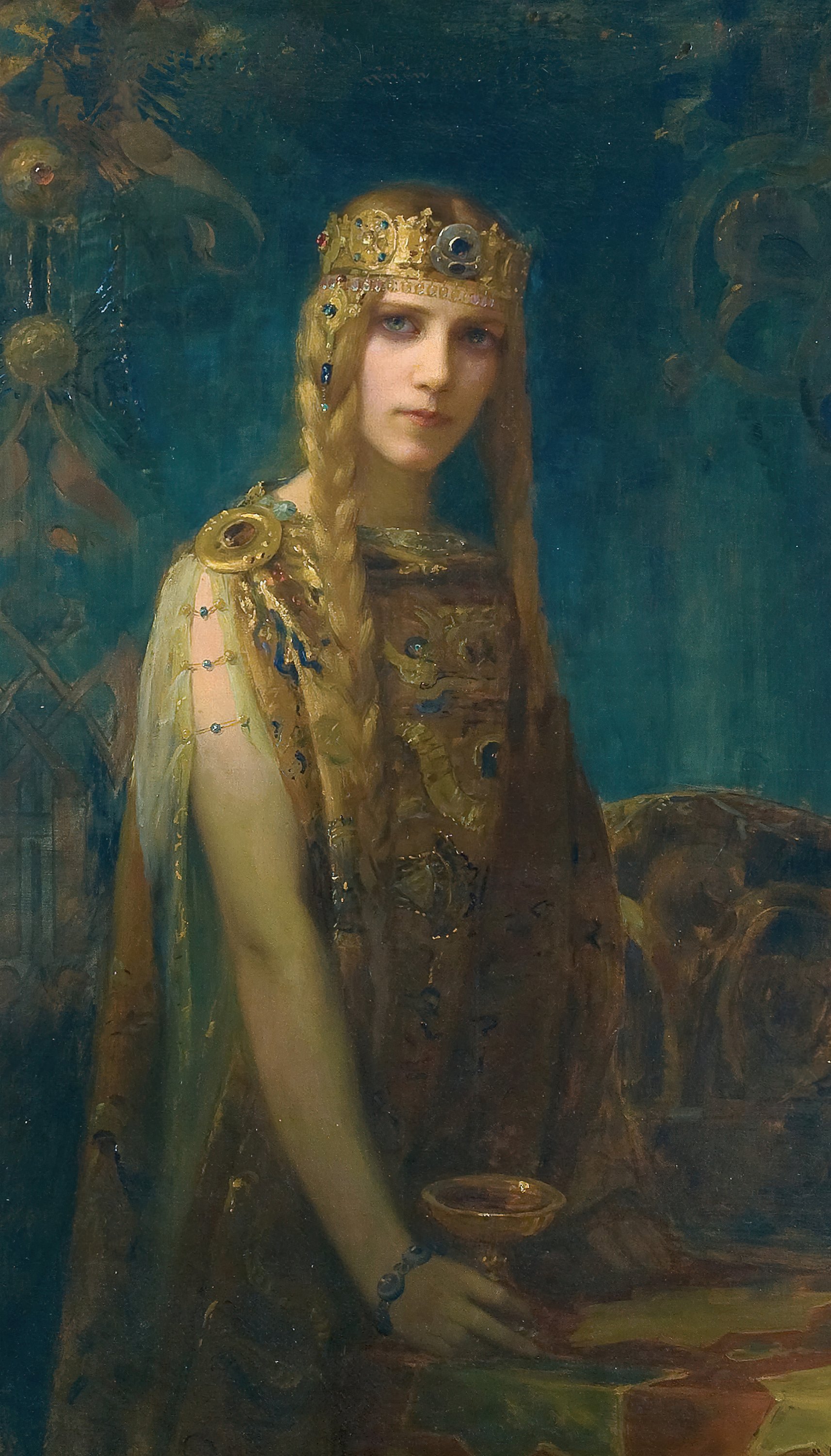

Tristan, Isolde & Marke, The End of the Song.—Edmund leighton.

Tristan and Isolde

The drama begins on board a ship that is carrying the knight Tristan and the Irish princess Isolde to the Kingdom of Marke of Cornwall. The two are already in love, but Isolde has been promised to King Marke in order to unite their kingdoms. After Isolde’s marriage to the King, a union that remained unconsummated, she continues her secret affair with Tristan. Together they curse the daylight and long for the veil of night and darkness to envelop them—a place where they may be free of the world and allowed to be united eternally.

The climax of the opera is found within the tragic Liebestod (Love-Death) scene. In these moments we detect the Buddhistic notions of the acknowledgement of the suffering of earthly existence and the impulse of world renunciation. From the words of Tristan:

“Descend, o night of love, grant oblivion, that I may live; take me up into your bosom, release me from the world! Extinguished now the last glimmers; what we thought, what we imagined; all thought, all remembering, the glorious presentiment of sacred twilight extinguishes imagined terrors, world redeeming”.

Eventually, the lovers are caught in flagrante delicto and in the upheaval that ensues, Tristan is mortally wounded by a sword from one of King Marke’s courtiers. On the brink of death, Tristan flees to his family castle in Brittany and is soon joined by Isolde. They die in one another’s arms and their eternal union is blessed by a mournful King Marke.

The Tristan Chord

Demonstrating Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of music, Wagner created the radical “Tristan Chord”, setting an explosion in the music world, and giving rise to the sounds of modernity. The chord contains two dissonances, only one of which is ever temporarily resolved. The moment one chord is resolved it is immediately replaced by the introduction of yet another dissonant chord. This illustrates that the attainment of the desired satisfies us only temporarily, it rather quickly shifts focus to the next desire. Some philosophers have conceptualized Desire as autonomous from any object or subject in the material world—a black hole, if you will, whose raison d'être is pure consumption, the embodiment of a pure lack or deprivation.

THE PRELUDE

the ‘Tristan chord’ first appears in bar 3 (at 0:09 seconds)

The effect of the Tristan Chord on the listener is characterized by an excruciating prolongation of one’s desire, an unsatisfying suspension that resolves a tension only to bring forth a new one. This build-up of tension over four hours of operatic drama finally resolves onto that final tonic chord that was willed from the outset.

THE CLIMAX

“Softly and gently, how he smiles, how his eyes fondly open—do you see, friends? Do you not see? How he shines ever brighter. Star-haloed, rising higher. Do you not see? [...and ends...] to drown, to founder – unconscious – utmost bliss!”

Day and Night Motif

Another manifestation of Buddhist thought in Tristan and Isolde lies in the conflict between day and night. At the most superficial level, the day reveals the lovers as two separate beings, forced to hide their secret love, and entrenched in a world of false values. The night outwardly represents the shelter of anonymity and secrecy, and the promises of Eros and the fulfilment of Desire. But at a deeper level, Wagner manifests Schopenhaurian metaphysics in the positioning of night and day. Schopenhauer distinguished between two realms: 1) the phenomenal realm of appearances, physical space, and light—in short, the world we inhabit and 2) the noumenal realm of undifferentiated matter, darkness, and unity. Tristan and Isolde are expressing a metaphysical desire. Their Love (the ultimate manifestation of Desire) can only be fulfilled in something that lies outside the bounds of life, and that of course, is Death. It is finally, at the tragic conclusion of the opera, that the lovers are eternally united through the attainment of that undifferentiated noumenal realm that is Death.

death of Tristan and isolde.—Rogelio de Egusquiza.

afterword: music and nature

References

1. Schofield P. Die Sieger and Die Wibelungen: How Parsifal is the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring. Religion & the Arts. 2013 Mar;17(3):246–70.

2. Magee B, Henry Holt and Company. The Tristan chord: Wagner and philosophy. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company; 2002.

3. Lü D, Wilhelm R, Jung CG, Liu H. The secret of the golden flower: a Chinese book of life. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World; 1962.